Stoker

“Did you ever stop to think that a family should be the most wonderful thing in the world?”

Stoker, Park Chan-wook’s superlatively beautiful film, is billed as a thriller, but isn’t quite. It’s more a style-heavy meditation on things not actually present in the narrative (it’s a vampire movie with no vampires), and a ruthless dissection of the thing that is (family, family, family).

Case in point: in the movie’s first moments, we meet India. She tells us she’s wearing her mother’s blouse, and her father’s belt, and a pair of stiletto heels her uncle gave her. We know nothing else about her. By movie’s end, everything in the shot has been given context, until the outfit is both a symbol of the family influences that take such a permanent toll on a child, but examples of a heightened, surreal specificity that characterize India throughout.

It’s difficult to go into some of the specifics, both because laying out plot points makes the storyline sound a little soapy (and hearkens perhaps too closely to Shadow of a Doubt – we’ll get there), and because pinning down a single concept for the threads robs some of the images of their power: “India’s father has recently died” is back-cover copy, and lacks the impact of bare walls painted ‘The Inside of Matthew Goode’s Irises Green’ from Sherwin Williams, and Mia Wasikowska’s face sliding in and out of grief by millimeters, and the endless, punishing sound of a hard-boiled egg being rolled across the table. The movie lingers on these, and lets the sense of dread and loneliness build until every image is steeped in it and the plot becomes only a frame on which to hang a story about a young woman in a small and rotten world that’s full of monsters.

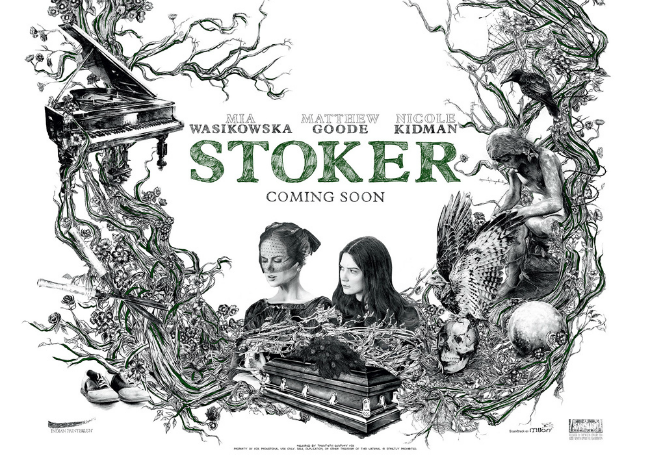

The slugline on the (intricate, disconnected, telling) poster is “Do not disturb the family,” one of many nods to Stoker’s thematic parent, Shadow of a Doubt – Hitchcock’s own family-circle Boy Creeps Girl, in which the mysterious Uncle Charlie rejoins his estranged family and strikes up an unusually intense relationship with his niece. However, in Shadow of a Doubt, the family’s essential goodness (hinted at in the top quote, in a moment of pique from our heroine Charlie) is what provides the horrific contrast to their sociopath relation, who realizes he’s been made by the person who loves him most, and so sets out to destroy his niece, on whom his hold is so complete she even bears his name.

Stoker looks through a darker mirror from the start, stripping away the idea that a family can be anything but disturbed, and suggesting that to bring evil into it only brings to light what was waiting (do not disturb the family); it only makes sense that the film unfolds in a succession of non-linear images and character beats that circle back, and repeat, and expand, until they become disturbing even if they didn’t start that way – every silent, lingering shot of wildflowers or tall grasses or pianos holds a dreadful secret.

And there isn’t a frame of this movie that isn’t perfectly balanced and tense. Even India reading in a hanging chair in the garden is composed like a trap (a trap that springs when her uncle, who had been a stranger to her until the funeral a few days before, shows up wearing her father’s tennis whites). But one of the movie’s most fascinating elements is the ways in which this dread and decay illustrate a character for whom the moral is extremely relative. India isn’t shocked by the revelation of darkness, but relieved; this family isn’t an apple with a worm inside, but a tangle of worms with no center at all.

Stoker arrived in theatres amid a haze of mystery, and dodging bursts of outrage from moviegoers who I guess never read up on Thirst or Oldboy or anything. True to form, Stoker features a heaping helping of incest (it drops all the sub- in this text) and the sort of restrained gore-porn in which blisters and broken necks are of equal abstract interest. However, the incest is played downright romantic for Park Chan-wook, and the only blood in the movie is on a young man’s lip just before a makeout session turns into attempted rape (not explicit, but one of the few beats in which things fall out according to the B-movie tropes the movie generally rises above).

Largely, however, Stoker is preoccupied with the collection of little horrors that make up this particularly broken family. It’s present in the food (the presentation of meals both as offerings and as traps), the clothes (filmy-schoolgirl chic and prep-monster dapper), the music (Clint Mansell’s score is gorgeous throughout, with a particular Philip Glass piano duet during which the entire theatre I was in held their breaths for the duration). Many of these moments are darkly comedic even in the middle of the grim; Nicole Kidman, as India’s desperate-housewife mother, provides several priceless-to-poignant reactions, and supporting characters (worried aunts, nervous Sheriffs) get to be nicely dry around the edges during their brief flickers of screen time.

But squarely in the center is India, who discovers her own potential for monstrosity in response to a monstrous world. Enter Uncle Charlie, dressed like a catalog and with all the preternatural calm of a vampire claiming a bride, played by an unabashedly creepy and hard-to-pin Matthew Goode. He first discomfits, then intrigues India, but it’s to the movie’s credit that India’s sexual awakening is only one facet of the greater, more lasting identity she fights to construct in nearly every frame. (It’s to Wasikowska’s credit that India, by nature a cipher, is so deeply and delicately portrayed; she’s hilariously sharp in dealings with outsiders, sympathetic in her moments of catharsis, and never less than riveting.) For once in this archetype, however, knowledge liberates, and with every spider a welcome friend and every pair of saddle shoes a talisman, the movie waits to see how she’ll define her family loyalties, and herself.

It’s not a perfect film; it shies away from one or two moment it seems to have been warned away from and makes explicit one or two things that seem reluctant to have been named, and some of the movie’s themes operate only as well as its dark-fairy-tale mantle allows for a sense of inherited monstrousness and supernaturally-connected inevitabilities. However, it’s an undoubtedly stunning film, and the alternately subtle and camp performances, the flashes of dark humor, and the fondly detached and amoral cinematic gaze combine to form a dreadful and compelling portrait of a very particular family tree.