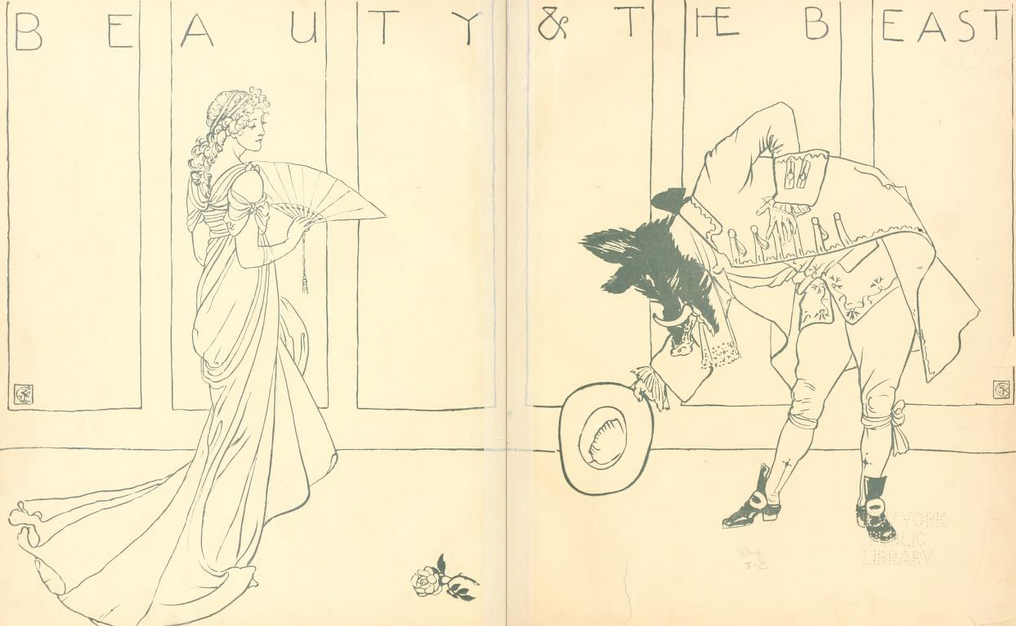

Beauty and the Beast

Well, the live-action Disney Beauty and the Beast remake has come out! And it turns out, I must have been waiting my whole life for this day, because all of March was basically me being unable to shut up about Beauty and the Beast in any form, for several reasons.

First up was the official review for Ars Technica; I had made a reference to “Something There That Wasn’t There Before,” but I appreciate that the actual headline makes no bones about my overall feelings. There are some bright spots (Luke Evans as Gaston is visibly thrilled to be breaking through at last, after stumbling through several other potential franchises), but overall it’s a flashy, echoing Disney experiment.

Does any of it work? Well, all this modernized polish certainly demonstrates the effective leanness of the original. Nothing highlights the emotional heart of a movie more than surrounding it with so much filler you can barely find what you came for. But with so little substance at its center, the rest of the movie defaults to a self-conscious scorecard just hoping for a net gain by the time the credits roll. Here’s the score: Kline’s worth ten points, and the grimly gleeful Evans is good for at least fifty, but Gugu Mbatha-Raw as Plumette the dancing feather duster is wasted, and those credits roll before Dan Stevens has shed his CGI for a five-dollar Handsome Prince wig—so subtract at least sixteen.

It is, however, a fascinating Disney experiment. Their live-action remakes have been coming closer to home, and Beauty and the Beast is the most faithful yet. How close it comes, and where it deviates, matter. A deviation that’s gotten plenty of press: Belle’s costumes, which have a relationship to the film that exists outside Jacqueline Curran’s 18th-century designs everywhere else.

It is, however, a fascinating Disney experiment. Their live-action remakes have been coming closer to home, and Beauty and the Beast is the most faithful yet. How close it comes, and where it deviates, matter. A deviation that’s gotten plenty of press: Belle’s costumes, which have a relationship to the film that exists outside Jacqueline Curran’s 18th-century designs everywhere else.

So, I wrote about Belle’s costumes and Being a Disney Princess, including Belle’s long history of being reimagined, and how Being a Disney Princess is a job that supercedes the story.

Beauty and the Beast is undoubtedly under immense pressure to live up to Disney’s biggest princess by offering something both recognizable and fresh, universal but distinctly Belle. It’s also under pressure to deliver a princess who can appeal equally to two generations. (Cinderella’s live-action ball gown was pitched to girls, while her wedding gown was marketed to brides.) It’s a level of self-awareness that invites cynicism: Belle’s “celebration dress” is so blatantly modern that it’s hard to imagine it as anything but a blueprint for another limited-edition wedding dress; certainly nobody wearing it is trying to evoke the 1780s — Belle least of all.

Bonus: I got to talk about Andreas Deja’s concept art, which I’ve always loved; lovely, evocative character design in this sketch.

But beneath the Disney story is the fairy tale it’s based on, which has at its center some very interesting questions about power and consent that Disney has played fast and loose with. (The new movie seems aware of the constraints but unable to break from its older template to do anything about them, which again is fascinating to watch even if it ultimately proves unsatisfactory.) At Vice, I wrote about the 1740 Villeneuve tale that became so famous, consent as a fantasy element, and the ways the Disney version tips toward a dark retelling.

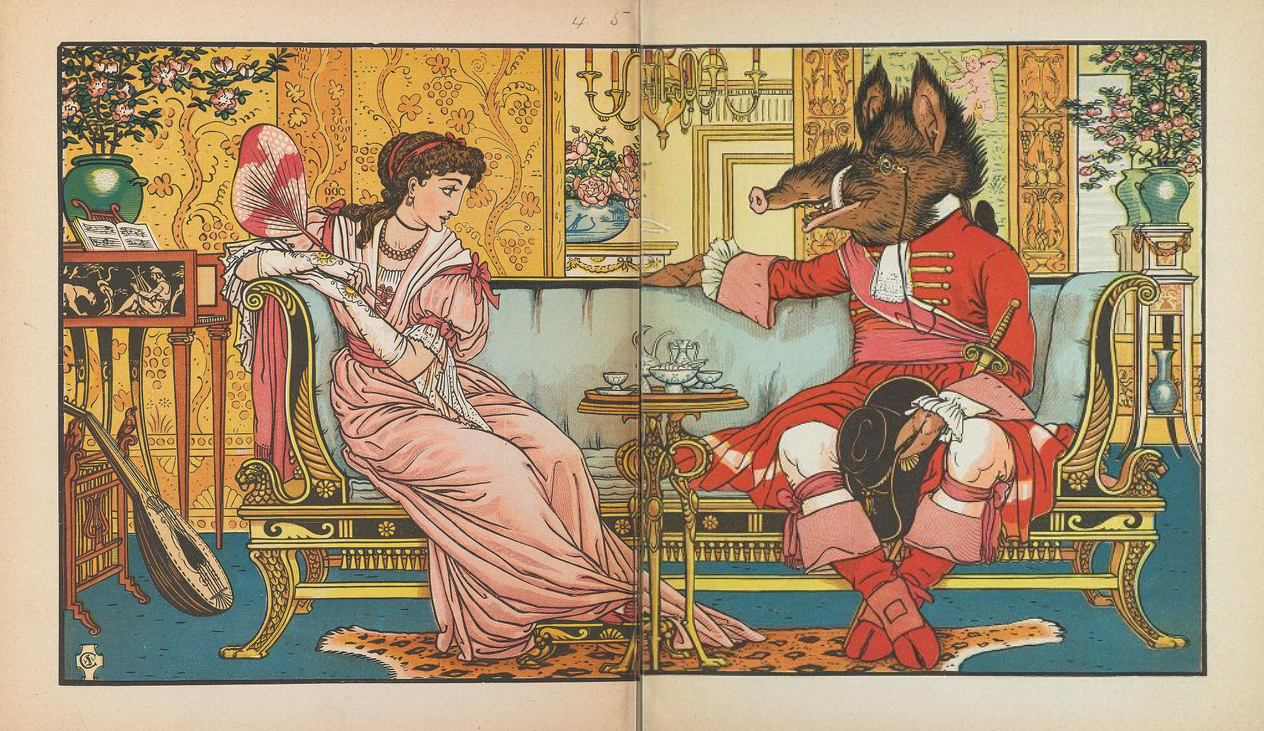

To understand the importance of this, look backward. There are echoes of earlier stories in Beauty and the Beast, most obviously the Cupid and Psyche myth, with its enchanted groom, quest, and magical tasks. But while Beauty and the Beast bears some parallels, it’s emphatically more domestic in scope. A merchant family’s city-to-country exile is an everyday misfortune, the bulk of the story takes place in the Beast’s house, and Beauty’s only magical task is to return from a family visit in the time she’s promised. The story needs no quest; it has a marriage.

On the other hand, Disney’s version is dark by mistake rather than by design; there are plenty of dark versions of the loathly bride or bridegroom that leave Disney in the dust. (The bride with the animal skin crosses a notable number of places of origin; men must have needed leaving all over the place.) Maria Tatar’s new collection of Beauty and the Beast variants was nicely timed to the movie’s release, and Tanith Lee’s posthumous collection is scheduled for release in April (and boy, if anybody knows how to take a story and make it darker, it’s Tanith Lee). I got to talk about both of them in the wider context of retellings over at NPR.

The Aarne-Thompson archetypes help us understand what connects the disparate versions of Beauty and the Beast; they’re all stories of searching and longing. But the tale resists a definitive telling — because at heart, it’s psychologically preoccupied with trust, power, and change, which makes it a hard story to pin down, let alone guarantee a happy ending. By admitting the power of the individual in a relationship, these tales understand that this power can become abuse. (Sometimes all a princess can do is steal back her identity and bail.) It’s why there’s such visceral appeal in dark retellings; we understand just how close love is to a horror story.

I still remember my first time seeing the animated Beauty and the Beast as a kid; it was, among other things, the first movie where I was old enough to want to know how the movie had been made. I’m not sure I can be glad of the remake in any artistic particular (and since Disney’s apparently greenlit 19 more, I’m even less enthused), but it’s one of the stories where any adaptation or retelling has something to tell us; for that alone, it will always be one of my favorites.