The Ghosts in Their Lives: The Hour, Season 2

Sometimes a show is so good you just wish it were better.

Sometimes a show is so good you just wish it were better.

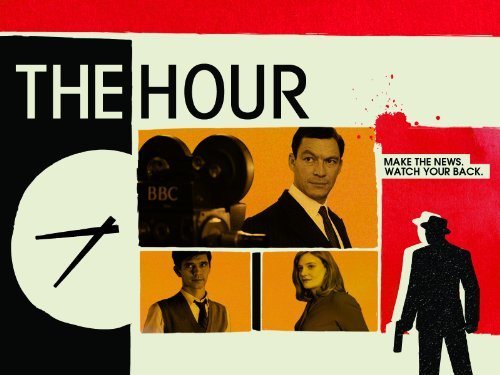

The Hour, a BBC miniseries-series we could really use a better term for, returned this winter for a second season of shenanigans behind the scenes of a late-1950s BBC newsmagazine. It comes into the lineup with several advantages, besides the momentum of a critically-successful first season. Its 6-episode format means it can frame a single Big Story, which helps keep focus tight and allows tertiary plots to be heavier on character beats. It’s written almost without exception by creator Abi Morgan, a double-edged sword of singular authorial voice. And it has a universally excellent cast. This last point is The Hour’s greatest draw; this is not an “excellent” cast in that they’re all good; this is an “excellent” cast in the true sense, and they give the show an addictive and ineffable confidence that alone would be worth watching for the whole season.

This doesn’t mean the show’s without mistakes. In fact, given these advantages, it makes a remarkable number; they’re the mistakes of a good show missing out on greatness – both easier and harder to forgive. (This show is its own “Yes, but…”)

The Hour’s first season (of which I spoke more here) centered not on the burgeoning Hour, but on journalist Freddie Lyon’s investigation into the murder of a society belle. Longtime friend and crush object Bel Rowley headed up the behind-the-scenes plot producing The Hour, into which Freddie’s investigation increasingly bled. The news team (particularly sharp-mess anchor Hector Madden and seasoned foreign-desk alcoholic Lix Storm) actually provided the season’s most honed and compelling character beats, but that’s what happens when you let Dominic West and Anna Chancellor do anything, and it was still true to theme. Themes were so focused, in fact, that the show was able to use crossword puzzles as a singular through-symbol for a season’s worth of production machinations, emotional blackmail, and espionage.

Season 2 has a central investigation – exposing the underworld blackmail ring operating out of Soho nightcub El Paradis (providing a handy set piece for beautifully-shot debauchery). Hector, a rising-star member of the club, finds himself in hot water there; as the Hour crew looks deeper into the club’s practices and clientele, they realize the recent NATO summit Lix has been covering might be coming closer to home than they expected, if certain politicos have been double-dealing on trips to the El Paradis. The plot is well-handled, though a stalwart of the genre. Without the first season’s narrow focus on theme, however, it’s in the subplots that this season sinks or swims – and it does both, often in the same episode. This gives us a season both intriguing and mystifying, leading in equal parts to beautiful character arcs, wasted thematic opportunities, nuanced examination of tropes, and one of the most singular attempts to make a silk purse from a sow’s ear committed to film this decade. And yet, amid this, parallels begin to emerge – of broken people, of missed chances, of things that can’t be mended – and begin to bring The Hour to light.

Last year’s romantic angle leaned strongly on the often-toxic intimacy of Freddie and Bel; Bel had a fling with Hector that left Freddie at Full Pine, but by season’s end the dewsome twosome were on even footing again, with Hector admitted as an honorary member of their confidences. Bel and Freddie spend most of this season with their respective relationship Macguffins (he has a charming French wife he brought home from BBC-imposed vacation; she halfheartedly flirts with a poaching ITV producer, to which Tom Burke brings all the urbane charm possible when your role might as well be titled Mr. Plotgateux), with Bel pining back for Freddie this round. In the final episode, the extent of her regrets are revealed in a letter she never sent, one that admitted everything Freddie could have ever hoped, just as he lies dying on the lawn outside their shared fortress. (Yikes.)

Hector, meanwhile, comes into his own in one of the most successful subplots this year: the personal growth of Hector and his wife, Marnie – just barely parallel. After Hector’s arrested for a sex scandal, Marnie, having had quite enough, covers for him one last time, then uses his name recognition as a springboard for her own ITV cooking show (proving she’s as adept as business as she is as coq au vin, and that she and Hector share a practiced façade more than they think they do). Hector, well aware it’s her turn to find happiness, begrudges nothing, and wrestles with several of his own unresolved demons, especially war-buddy-turned-cop Stern, who’s responsible for beating showgirl Kiki Delaine – the crime for which she originally pinned Hector.

That Kiki isn’t demonized for the falsehood – by the text, by anyone at The Hour, by Marnie, or even by Hector – is one of the show’s triumphs. It’s made clear the objectification and powerlessness under which the showgirls work; lashing out publicly to warn off your beater privately is presented as an unfortunate but necessary survival tactic. (Hector’s later relationship with Kiki, which shifts subtly into mutual respect, is one of the best grace notes of the season.) By the time she takes her seat for a fateful broadcast in the final episode, we understand what’s at stake for Kiki if she speaks – or if she stays silent.

That the question of her appearance on the show should be so nail-biting is evidence of the skill of the production as a whole- editing, music, lighting, framing all enhance the superlative acting and make you worry desperately, in the moment, about things that are foregone conclusions on paper; it’s one of the things the show can do markedly well.

Sadly, it doesn’t always. The secondary story for The Hour’s domestic desk this year ostensibly examines racism; however, it’s handled with a heavy and perfunctory hand. Office secretary Sissy’s fiancé, a doctor in Notting Hill, is called on to be the model minority in an on-air debate with a fascist; afterward, he vanishes from the narrative, having solved racism forever, I guess. (A scene in which Sissy confides to her friend Isaac that her family disapproves of the marriage was actually cut from the American broadcast. Racism really IS over!) And Costa Rican showgirl Rosa, the first to come forward about Cilenti, DOES vanish – she’s killed for her trouble. And while it would be unrealistic to ask that your ruthless underworld blackmailer not kill anyone, or that one news conversation change the minds of all British fascists, this glossing-over is one of the points at which you wish the show was working on the level it clearly can.

Perhaps NATO deliberations might have made for more effective background noise, in that case, but Lix Storm’s newshounding is wholly eclipsed this season by the arrival of new production head Randall Brown, a tense but savvy newsman whose eye for good television is unerring – and whose business with ex-flame Lix is unfinished.

And it’s here that the show provides both the agony and the ecstasy. If I said, “Lix’s ex-flame is back, and tries to rekindle the relationship by searching for the daughter Lix gave up for adoption, and after a lovely red herring halfway through the season they realize she was killed in an air raid in World War 2 and then they are sad as hell,” you would say, “That is B-grade soap opera plotting,” and you would be absolutely right. However, Anna Chancellor and Peter Capaldi are such consummate actors with such startling chemistry that even their throwaway conversations are magnetic, and the pent-up energy of their shared scenes are, quite frankly, more effective drama than anything around them.

Randall’s obsessive-compulsive disorder turns into a window to his strangled emotional state; Anna Chancellor, who delivered a standout performance last season, gives what might be the performance of her career in this one, as Randall’s presence quietly cracks her devil-may-care persona and forces her to examine an unhappy past – one we glimpsed last year, when she stole the series with a one-minute monologue about a particularly painful snapshot. This year, her halting explanation of Not Looking for her daughter vies for the most powerful 90 seconds of the season, against Randall’s utter breakdown upon learning of their child’s death.

The ecstasy! that aspiring actors have such scenes for mandatory viewing; every silence speaks volumes, every word cuts deep. The wry understanding that sometimes appears despite their best efforts peppers what’s otherwise unbearably melancholy. Chancellor can deliver a poison look or struggle to hold back tears like none other; at the end of Randall’s breakdown, Capaldi drops to his desk so powerfully he falls clear out of frame before the camera can catch up.

The agony! that Lix’s only subplot this season (such private business practically seals the pair of them in a bubble) should be romantic, and that it should be this particularly-gendered trope of Lost Motherhood; that it should obliterate her journalism so much that she actually suggests Rosa’s death might be an accident, which is so painfully out of character you can hear the needle skipping; that Capaldi’s admittedly-magnificent pain should be the focus of the text, and that Lix – with equal claim, if not more, to this heartbreak – should be sent so often to comfort; that the door shuts, literally and repeatedly, on Lix’s suffering, which is relegated offscreen. If the show rates another season, one hopes for better at the same time one hopes for more.

One hopes for more of everyone, come to it; this show’s characters are well worth following, even when they’re having to elevate their material. Bel and Freddie (still every bit the fantasy characters from Season 1 – marvelously acted, but lacking any hamstrings of reality) took a step towards romance just before Freddie gets swept up by Cilenti for the beating of his life; though they’re at their weakest as a couple, it would still be worth watching. In fact, they might be more interesting after everything falls apart – Freddie and Lix, after a brief fling in Season 1, have a fond rapport, and Hector and Bel’s friendship is twice as compelling as their affair ever was. And Hector’s newly honest relationship with Marnie creates a tentative understanding that hints at better things to come, if we get them. But we might never get them – and somehow, that feels like the point. None of the characters get to make the amends they want to; they do what they can, if the past allows, all the while aware that things may never fully heal.

If this season has a theme, then, it’s best delivered by Kiki herself, explaining the delicate ecosystem of honeytraps that’s made Cilenti and Stern rich men; “We’re just the ghosts in their lives,” she says, “they shouldn’t be surprised when we come back to haunt them.”

Though the subplots are disparate, and some disappointing, this season leaves us wanting more, largely because, as it builds new relationships on the ruins of the old, it examines the power of unspoken things; things left undone and unsaid, the threat behind what’s hidden. In fact, these things have an almost magical power; there’s an element of fantasy behind the final broadcast that goes beyond the studio lights. The ghosts of the dead can be laid to rest if their murderers are named; the ghosts of past love can be resurrected. In The Hour, though the vise tightens and curses close in, the person who speaks truth in front of the camera at the critical moment breaks the spell, and sets everyone free.

It’s enough to carry us into another season; it’s enough to leave us with a full studio of ghosts.