The Girl Stays in the Picture

Eight Silent Films and the Women Who Made Them Legendary

The silent-movie boom of the early 20th century left an indelible mark on pop culture, and is perhaps the cinema era that cinema loves best. From Singin’ in the Rain to The Artist, Hollywood often returns to those seemingly-halycon days of dashing men who made movies happen, and ingenues they loved.

It’s a familiar picture, but it’s missing something. The women of silent film, though often referenced in style, are largely forgotten in their substance: the power they wielded behind the scenes, which was often formidable, and which the studio system of the 1930s couldn’t forget soon enough.

But women were the backbone on which Hollywood was built; the biggest screen sirens shaped everything from pop culture to politics, with behind-the-scenes maneuvers that left their on-screen antics in the dust – down to founding studios of their own.

Below, eight seminal silent films, and the awesome women behind them.

Cleopatra (1917)

Cleopatra (1917)

In an age that favored ingénues, Theda Bara was a femme fatale – by design. One of cinema’s first PR victims, Bara (born Theodosia Goodman) was instructed to espouse the occult in interviews, and some contracts included riders dictating she be veiled in public and only leave the house at night. Nicknamed “The Serpent of the Nile,” studios claimed Bara was raised in the shadow of the Sphinx by artist-nobles. (Real place of birth: Ohio, close second in mystery to Ancient Egypt.)

Her career remains equally mythic; all but two of her films are lost. Her legend has been largely reconstructed from ephemera like stills from Cleopatra, with Bara draped in filmy robes that movies only got away with until enforcement of the Hays Code starting in 1934, which put the kibosh on those transparent shenanigans.

It’s not much to go on, but her effect was lasting; during her box-office reign, studios became femme-fatale-farms, desperate to find the next Theda. And they did: Pola Negri, Nita Naldi, and Louise Brooks found success in the niche Bara created, and her influence is still seen in all those vicious vamps in drapey dresses.

Highlight: Celebrate the Halloween season with the twenty spooky seconds of Cleopatra that remain; Bara works a beaded bra and gives sneery bedroom eyes to some lucky soul we never see.

B-roll: Bara truly is a silent star. She stopped making pictures before the advent of sound; unlike many actresses who tried talkies, Bara never spoke a word.

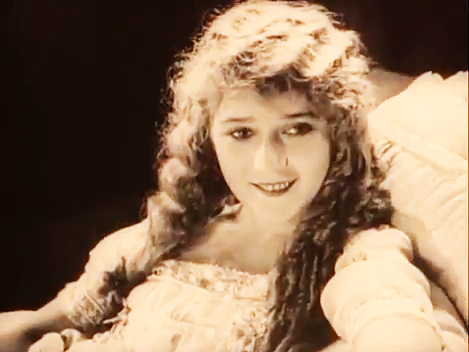

Stella Maris (1918)

Stella Maris, a melodrama about a paralyzed teen heiress, the married man who loves her, and the orphan that looks suspiciously like her and perishes conveniently in the last reel, was the springboard to stardom for Mary Pickford.

Pickford cut her teeth on nickelodeon one-reels, and when she moved to features she was primed for the game. Stella Maris cemented her hyper-innocent persona, but behind the Little Girl Lost was a visionary business mind – she was one of the first actresses to negotiate for a cut of the profits, and by the time Stella Maris premiered, she was at work on her biggest venture: United Artists.

UA, formed in 1919 with Douglas Fairbanks, D.W. Griffith, and Charlie Chaplin, was the first actor-run studio, allowing them to make and distribute films independently. Though the venture faltered after talkies, it inspired other actresses to take control of their careers and challenge the burgeoning studio system.

Pickford’s magnetism was pivotal to her success, and it’s hard at work in Stella Maris. One of the first to understand that film required a subtler approach than stage acting, she goes for naturalism and the camera loves it, making this soapy marvel more watchable than it has any right to be.

Highlight: To celebrate spring, Stella’s parents furnish her with half a dozen children who must skip around a Maypole for her entertainment. They’re not thrilled.

B-Roll: Stella Maris was penned by Francis Marion. This was their third pairing, and she’d write another half-dozen films for Pickford, as well as vehicles for Anna May Wong, Lillian Gish, and Greta Garbo, making Marion one of the most prolific and powerful screenwriters of the era.

Within Our Gates (1920)

Within Our Gates (the first full-length feature directed by an African-American) is an unflinching response to Birth of a Nation, examining racism in both North and South; the movie was banned in several cities for fear it would instigate riots. Due to a tight budget (and despite editing tricks ahead of their time), it lacks some polish. However, Evelyn Preer’s performance as Sylvia Landry, who goes North to raise funds for a school, elevates it to a poignant character study. (In a chilling scene, she’s ‘saved’ from rape when her white attacker sees her birthmark and realizes she’s his daughter.) But notably, the film avoids making Sylvia a Tragic Mulatto – conversely, on every point she triumphs, and ends the film with funding and her true love both in hand.

Within Our Gates (lost for decades before rediscovery in a Spanish theatre in the 1970s) was the first of half a dozen Preer collaborations with director Oscar Micheaux. Most are lost, but Preer had a reputation for versatility and appeared in numerous well-reviewed stage turns, tantalizing hints of a talent who died before she became the mainstream success she could have been.

Highlight: A tie between two very different moments. In the first, Sylvia chats with the smitten Dr. Vivian, her charm lighting up the screen; in the second, Sylvia’s family flees a lynch mob in flashback, intercut with newspapers’ bald lies.

B-Roll: Part of Greer’s spontaneity (and some of the more casual performances) is because the budget allowed for only one take of each setup.

Blood and Sand (1922)

An inheritor of the Bara mystique, Nita Naldi had the face of an empress. Her cinema summer was brief – she walked on her contract with Famous Players-Lasky, and her career never recovered. But while she had the screen she burned it up, vamping her way through a dozen films, simultaneously seductive and camp.

She came to notice in 1919’s Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. As dance-hall girl Gina, she had to entrance John Barrymore so he’d turn to dark science just to woo her. (It worked.) With vamp in vogue, she starred opposite Rudolph Valentino in Blood and Sand, a historical epic about a bullfighter, his long-suffering wife, and Dona Sol, the rich widow who sets her sights on him. Hand-wringing and heavy eye makeup for everyone!

The Valentino-Naldi combined bone structure was so successful they made three more (one, The Hooded Falcon, is unfinished), but none captured the public like Blood and Sand, which remains one of the smoking-hottest pairings in silent film.

Highlight: A dead heat between their first fight (including broken vases and fainting fits) and Dona Sol’s initial seduction of her conquest, featuring sloe-eyed harpistry (actually happens), pained stares, and the immortal pick-up line, “What wonderful arms you have – your muscles are like iron!” (Get it, Nita.)

B-Roll: Naldi missed her calling in the Vicious Circle; from interviews in her heyday, it’s clear that if you needed a biting comment on the record, you could give Nita a call.

The Wind (1928)

When looking for an innocent flower, you didn’t get ingenue-er than Lillian Gish. Her dinner-plate eyes devoured the camera whole. She was one of the most successful actresses of the age, and no stranger to controversy – as a favorite of D.W. Griffith, she had the dubious honor of featuring in both Birth of a Nation and Broken Blossoms, two of the most eyebrow-raising flicks ever made. But to the public, she could do no wrong.

The Wind is an example of the control Lillian had over her career, at a time when actors’ power was already waning against studios. Gish chose the novel, director Victor Sjostrom, and costar Lars Hanson (who she’d seen in Gosta Berling with Garbo, and imported in 1926 to star with her in The Scarlet Letter).

The film follows Letty, visiting brother Beverly on the Texas sand flats. Men line up to seduce and/or propose, and Beverly’s jealous wife throws Letty out. Lonely (and disturbed by the haunting wind), Letty marries kindhearted Lige, who, disabused of the notion that she married him for love, leaves Letty to her increasing wind-madness. The passionate leads help sell the last act, where you can almost see producers shoving people into frame to change the original denouement (Letty’s death via sandstorm) into something more romantic. So, the movie ends with the lovers in the open doorway, being sandblasted right down to the bone like it’s no big thing.

Highlight: The wedding night plays out in excruciating detail; in between the fichu-clutching and hand-wringing is subtle character work that illuminates both oppressed Letty and heartbroken Lige. (Dare you not to wince when Lige looks into her water pitcher and sees the coffee she’d pretended to drink.)

B-Roll: Highest face-clutching per capita of any Lillian Gish film.

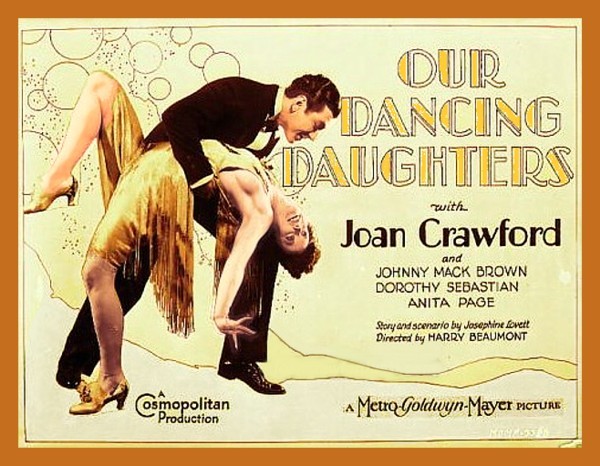

Our Dancing Daughters (1928)

Before Joan Crawford was a caricature of herself, she was cinema’s epitome of the brainy flapper – a mountain she worked to scale. From her early days as a feature Charleston dancer who hit the party circuit to be seen by the right people, Crawford had her eye on whatever it would take to make it big. (One of the reasons she made such a smooth transition to talkies is because she’d been working on diction for years.)

The film that made her a star was 1928’s drama Our Dancing Daughters, an exploration of the flapper lifestyle that gave depth to the image of the party girl. Make no mistake, Crawford parties (Blair Waldorf only wishes she had this social life), but her fiery Diane has steadfastness under her flirty core. When her beloved, Ben, thinks her carefree attitude means she doesn’t care for him and marries her best friend Ann, she resists all his post-marital advances, though she knows Ann’s unfaithful. It isn’t until drunk Ann falls down the stairs (oh, movies) that Diane agrees to reconcile with her fickle Mister. It was a good old-fashioned morality play, determined to prove that giving ladies the vote hadn’t turned them all to Bacchae, and just as Joan calculated, the vivid Diane turned her into a household name.

Highlight: During a garden party that turns into a for-fun horse race (as you do), Diane hangs back and asks Ben to fix her saddle, leaving the two of them alone. “There’s nothing wrong with your saddle,” he says, to which she lights up a cigarette, glances at him through her lashes, and says, “I know it.” (Get it, Joan.)

B-Roll: Crawford really was single-minded about making a place for herself in the mind of the public; she even made the choice of her stage name a magazine contest. It became a household name – one that she always disliked.

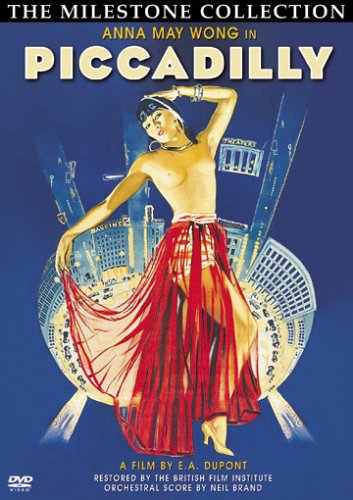

Picadilly (1929)

Picadilly (1929)

To emulate Anna May Wong’s career, line up a series of brick walls, then run through them. She starred in Hollywood’s first color picture, The Toll of the Sea; she had “close friendships” with men and women, including Marlene Dietrich; she started a production company (though a corrupt business partner scuttled the venture); she spoke openly about widespread racism in a Hollywood that hired white actors to play Asian. She was so frustrated with the latter that at the end of the decade she headed to Europe, where her biggest star turn came in 1929’s Piccadilly.

Wong plays Shosho, a dancer whose talent brings her to the attention of club owner Wilmot, who puts her front and center onstage and pursues her behind the scenes. Since Shosho has a jealous ex, Wilmot has a jilted lover, and somebody has a gun, things are bound to get soapy. The charismatic Shosho is doomed, though the quest to find her killer is abrupt and awkward. (No one wants to admit they picked up a gun, fainted, and have no idea how the body got there. That alibi is nobody’s friend.)

Highlight: Shosho and Wilmot hit a nightclub where the owner throws out an interracial couple. The woman berates him for being a hypocrite, and marches out to cheers from other patrons. In the shadows, a wary Shosho looks around, tense and heartbroken, as Wilmot suggests they leave before they’re made to leave. This shot alone proves that Wong was a magnetic and subtle performer.

B-Roll: Legend has it that Wong choreographed her dance scene on the spot. (For those who have seen the movie, this comes as no surprise.)

Pandora’s Box (1929)

Louise Brooks is one of the most iconic examples of the flapper; even those who eschew silent movies can probably pick her out of a lineup. Though she considered her life a tragedy, she was genius at cultivating an image; her screen persona, from her haircut to her careful carelessness, made her the toast of the town. Eventually she, too, would leave her studio over salary disputes and head for Europe, where the move that scuttled her Hollywood career gave her the opportunity to star in the film that single-handedly secured her legacy.

As Lulu, Louise Brooks saunters through Pandora’s Box, a drama that serves in equal parts as maneating potboiler and satire of the selective morality of the middle class. She seduces men and women alike, upgrades consorts at intervals, runs away from a murder charge, suffers a gambling fiasco, and eventually turns to prostitution, where her unfortunate choice of first client is Jack the Ripper.

Highlight: At Lulu’s wedding to a magnate, Countess Geschwitz takes a romantically-charged turn around the floor with the bride, in one of cinema’s earliest explicit depictions of lesbianism. It’s a brief scene, but Brooks and Alice Roberts make it memorably poignant. (Later, the lovelorn Countess stands up for Lulu in court, then supplies her own passport to help Lulu escape the country.)

B-Roll: When the Hays Code was being developed, Pandora’s Box was brought up often as an example of cinematic licentiousness that had to be curtailed; since Lulu meets an unhappy end that would technically have fulfilled the Code’s prescriptions for punishing provocative women, it seems telling about what worried people most in this portrait of a woman who did as she pleased.

Of course, these women, amazing as they are, are the tip of a cinema-history iceberg. The early days of feature film were a rare combination of technological shift and pop-culture gold rush that proved a fertile breeding ground for talent, and many women took full advantage of it both behind and in front of the camera. In fact, the height of silent films, after the mechanisms of filmmaking and distribution were widespread but before the solidification of the studio system, was arguably the period in which women in Hollywood had the most power over their own careers. It’s a contribution often forgotten by the industry itself; these eight women, however, left an indelible mark on the silver screen, and are well worth rediscovering.